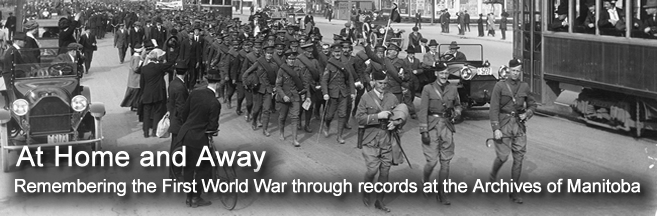

The 100th anniversary of the First World War is now finished but the records will continue to be preserved at the Archives and accessible to current and future generations who want to know more about the time period. In addition, this blog will remain on our website as an additional resource.

November 2017 Posts:

- 27 November: Military service exemption for farmers – a letter to the Premier

- 20 November: The S.S. Pelican

- 14 November: Messages by Wire: Telegrams from the Time of the First World War

- 7 November: 1918: the last year of the war

- 6 November: Cavalryman and diarist George Hambley at Passchendaele

27 November 2017

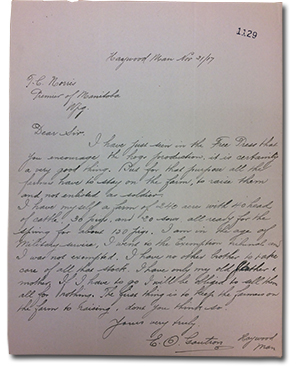

Military service exemption for farmers – a letter to the Premier

The Military Service Act was passed 29 August 1917 and introduced conscription in Canada. The new Act was a concern to Canadian farmers. Farmers had been tasked with producing more to support the war effort and were now being called to serve overseas as well. In response to these concerns, the law did not go into effect in farming communities until mid-October 1917 so that the 1917 harvest could be brought in. After that, individual cases were reviewed by exemption tribunals which determined whether the farmer was essential for carrying out the work on the land.

In a letter addressed to Premier T. C. Norris in November 1917, farmer E. O. Gautron [or Gantron?] notes that he was pleased to read in the newspaper that Norris encourages hog production but that this production is only possible if men can stay to work their farms. He has a farm of 240 acres in Haywood, Manitoba with 40 head of cattle, 30 pigs and 20 sows and expects to have 150 pigs in the Spring. He explains that he went before the exemption tribunal but was not exempted even though he does not have any brothers, has elderly parents and would need to sell the animals if he has to enlist.

Premier Norris’ response five days later states that he agrees with Gautron; “it is very important that the farmers do not be robbed of the necessary help”. He writes that he has discussed the matter with various government ministers who, in turn, took it up with Minister of Militia, General Mewburn, who recently made a statement (which appeared in the newspaper that morning) that men required on farms would not be called on to serve overseas.

He provides further reassurance that “in your case I would not think that there is any danger of your having to go to the Front.”

The statement made by General Mewburn on 24 November, referred to in Norris’ response to Gautron, exempted all farmers’ sons and experienced farm labourers so that they would be available for the 1918 planting and harvest. He also promised a review of any judgements refusing these people’s exemptions. This came during the federal election campaign of November-December 1917 and is widely viewed as an attempt to win the rural farm vote by Prime Minister Robert Borden.

This exemption for farmers was lifted in April 1918 because of the great need for more soldiers. It is not known what this meant for E. O. Gautron but his letter to the premier of Manitoba, and the response he received, can be read, one hundred years later, at the Archives of Manitoba in the government records series, Premier’s office files.

Search Tip: Search “Premier’s office files” in Keystone for more information.

Feedback

E-mail us at [email protected] with a comment about this blog post. Your comments may be included on this page.

20 November 2017

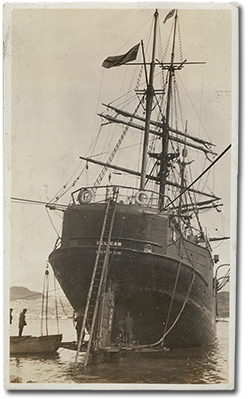

The S.S. Pelican

As the First World War entered its fourth and final year, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) continued its trans-Atlantic shipping and purchasing business with European allied governments, employing over 250 ships. Some of these ships, between wartime business trips, continued their usual Arctic runs for the HBC, supplying posts and transporting furs for the HBC’s Fur Trade Department. Others were temporarily taken away from their fur trade duties and were fully in the service of European governments. The S.S. Pelican was one of these ships.

The Pelican was bought from the British Admiralty in 1901 and converted into a cargo carrying ship. From 1901 to 1915, it was used to supply HBC posts in the Arctic and Labrador, and to transport furs back to London. In 1915, the Pelican was employed in taking cargo from New York to England. From December 1916 until April 1918, it was fully in the service of the French government. During August 1918, while on a voyage from Canada to Great Britain on behalf of the British government, the Pelican successfully fought off a German submarine. Watch for a blog post on this story in the coming year.

After the war, the Pelican continued to ship goods in Europe, sailing between France, England and Russia. In May 1920, it left Cardiff to return to its duties in Hudson Bay and Labrador. On August 4, while en route between Port Burwell and Lake Harbour, it got caught in fog and suffered irreparable damage from ice. This was the Pelican’s last voyage.

Search Tip: To find more images and other records of HBC ships, search the ship’s name in Keystone.

Feedback

E-mail us at [email protected] with a comment about this blog post. Your comments may be included on this page.

14 November 2017

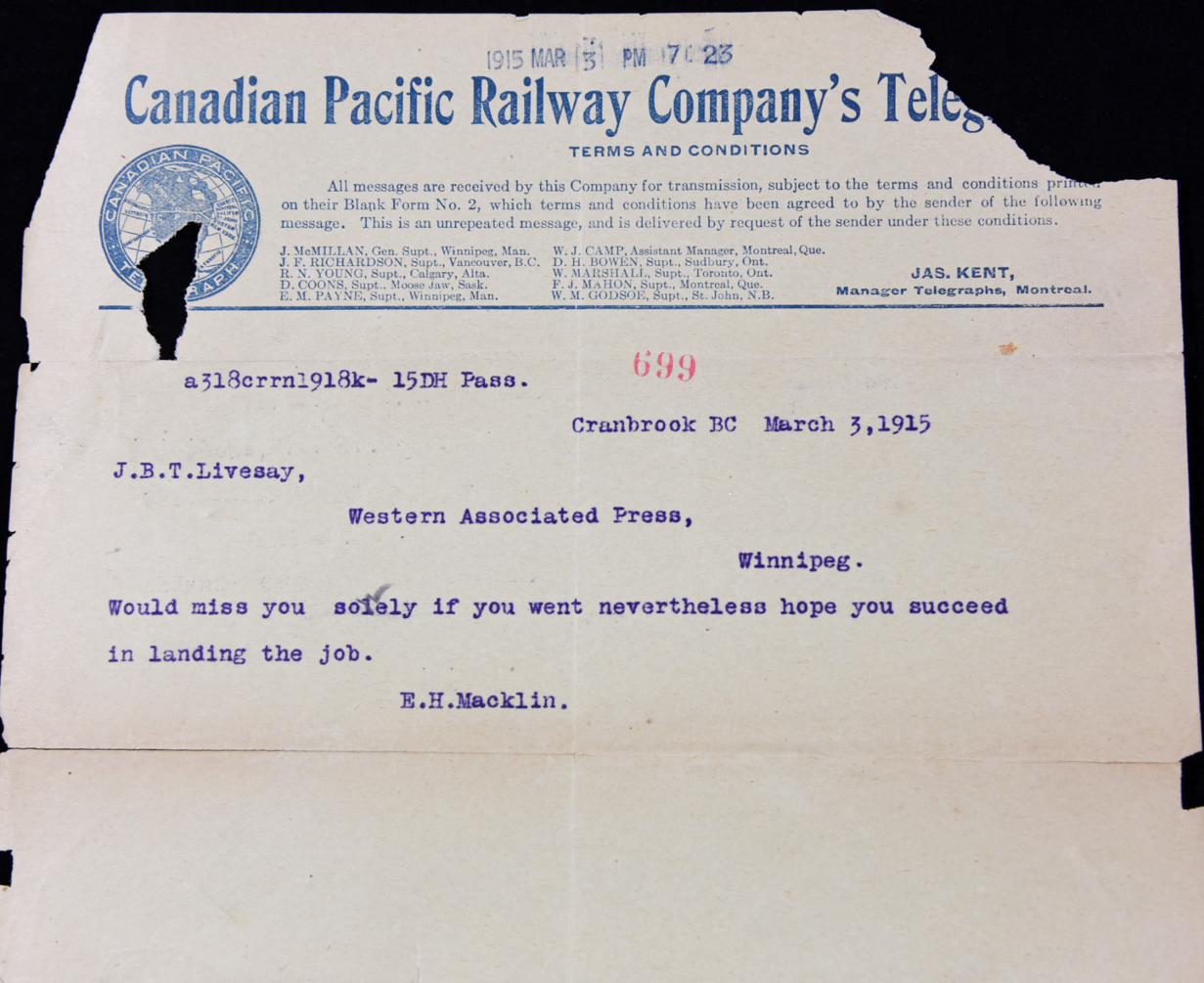

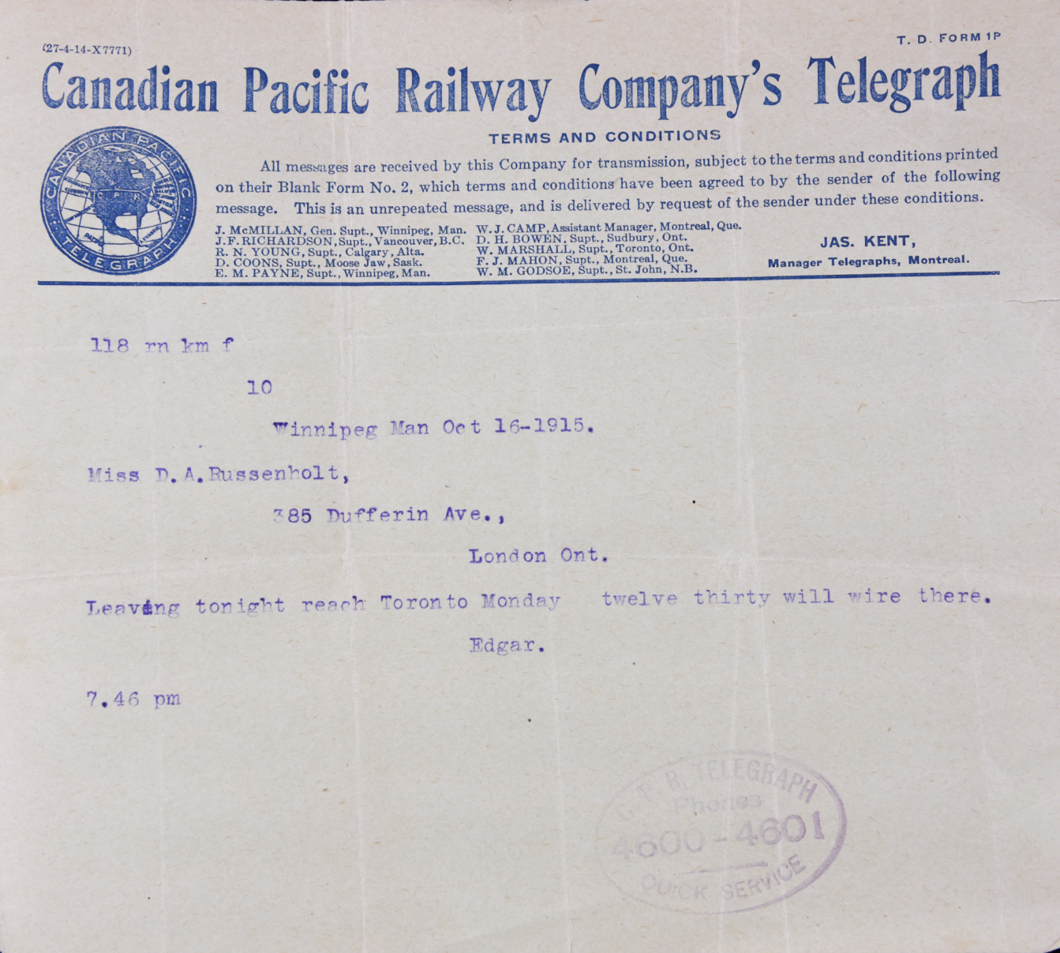

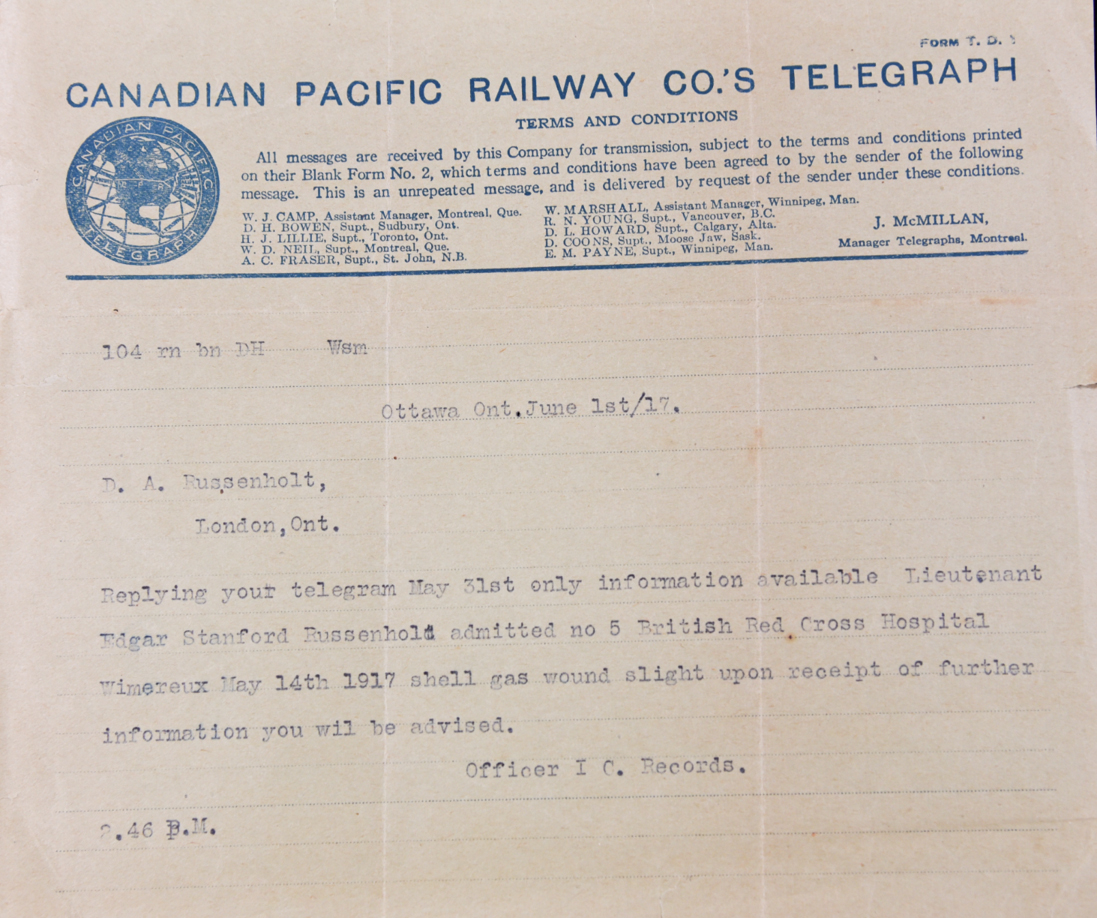

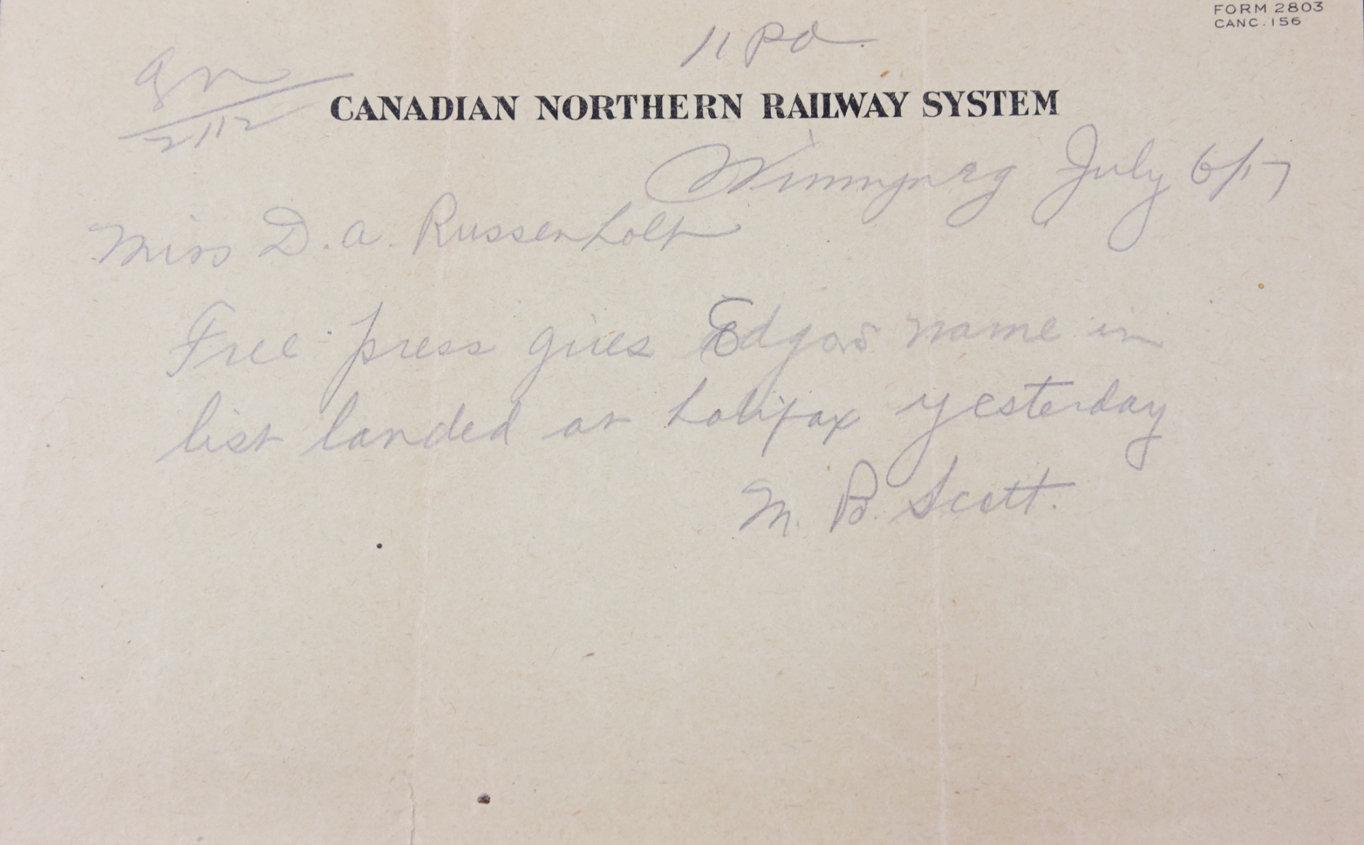

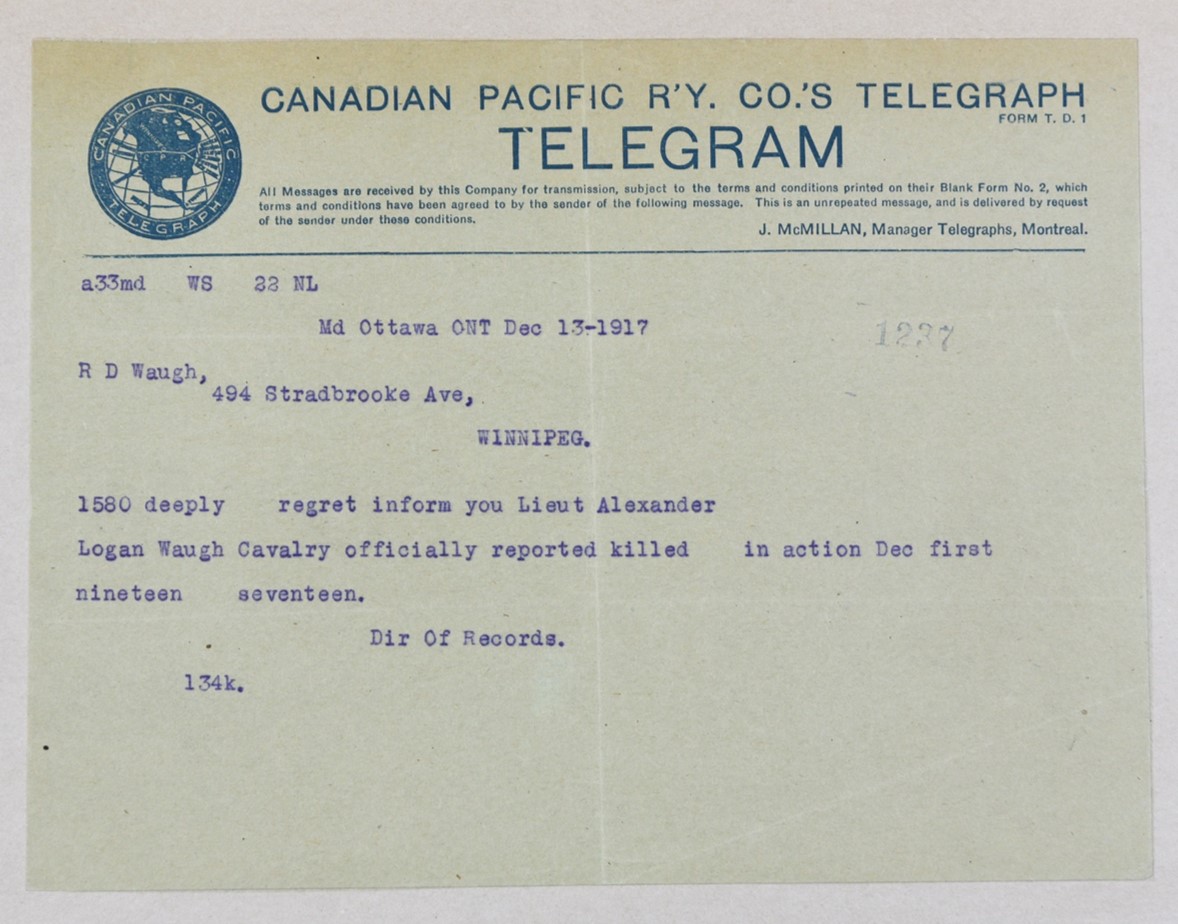

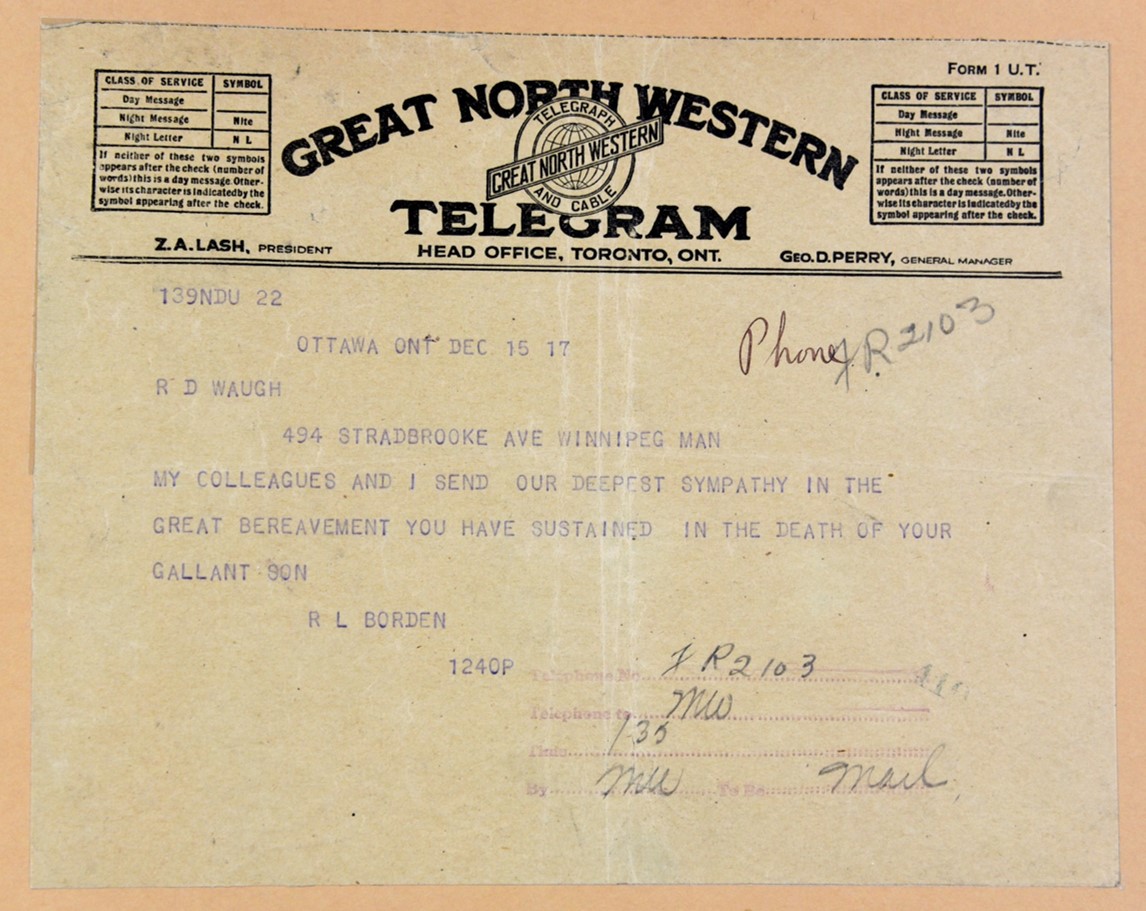

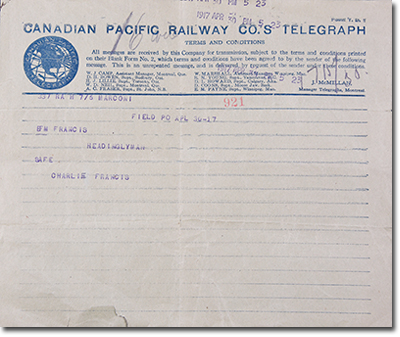

Messages by Wire: Telegrams from the Time of the First World War

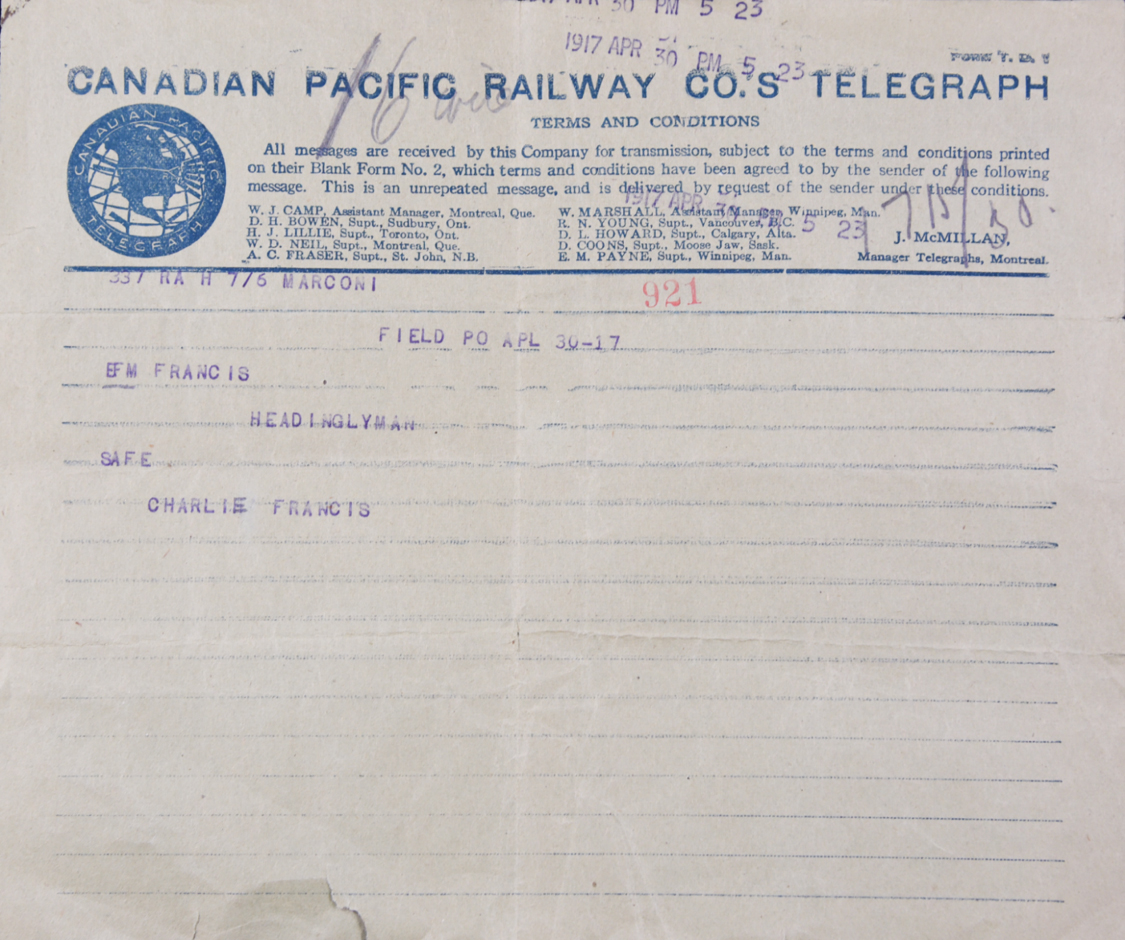

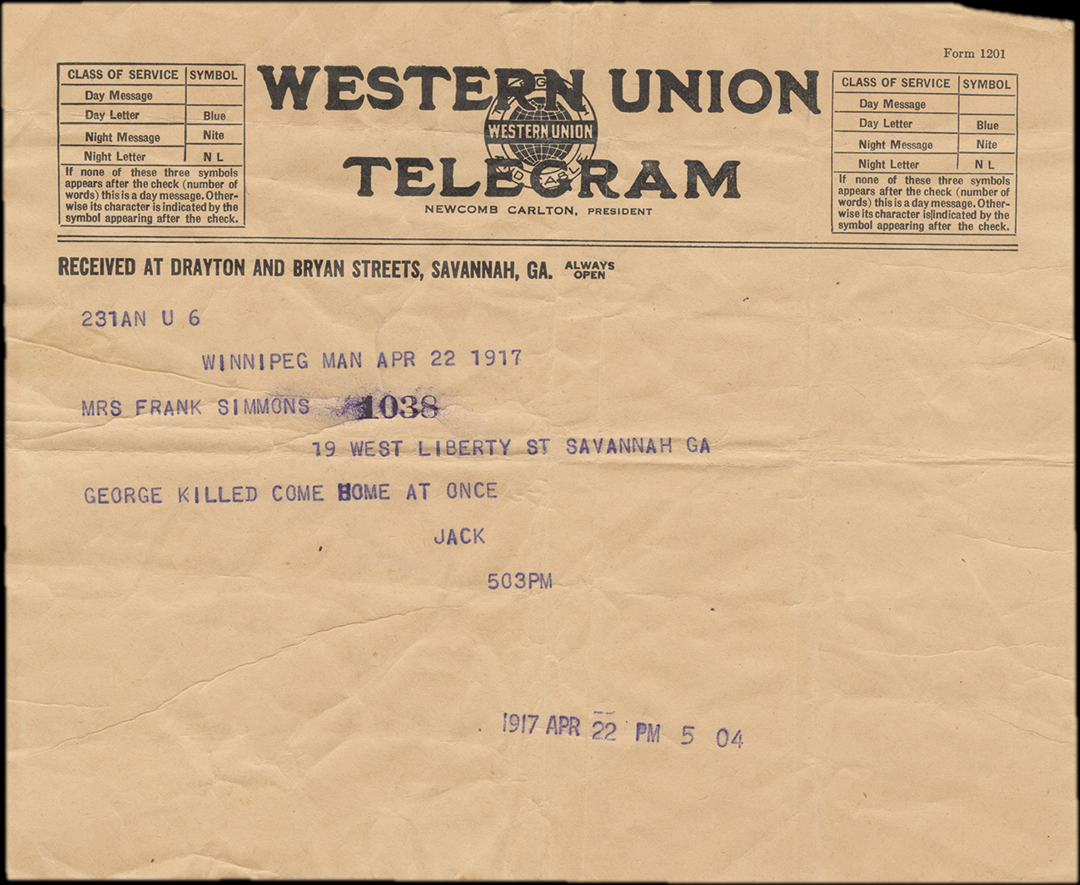

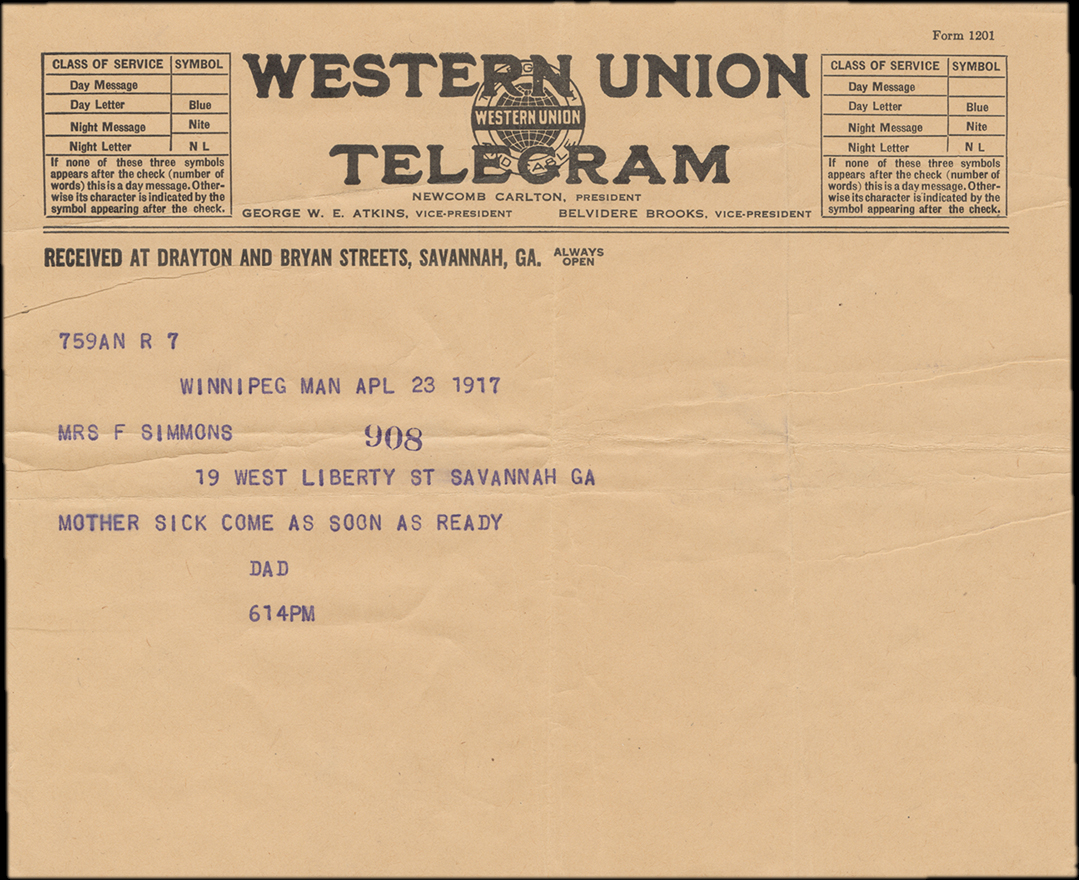

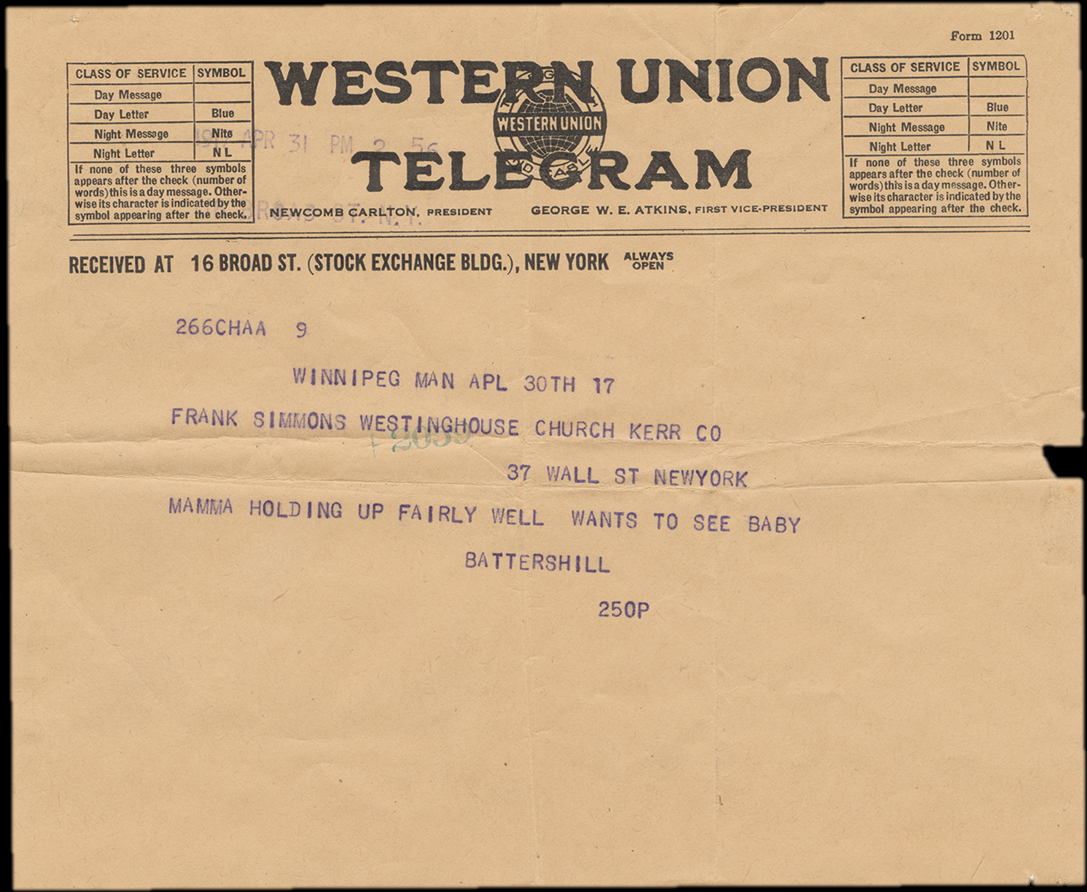

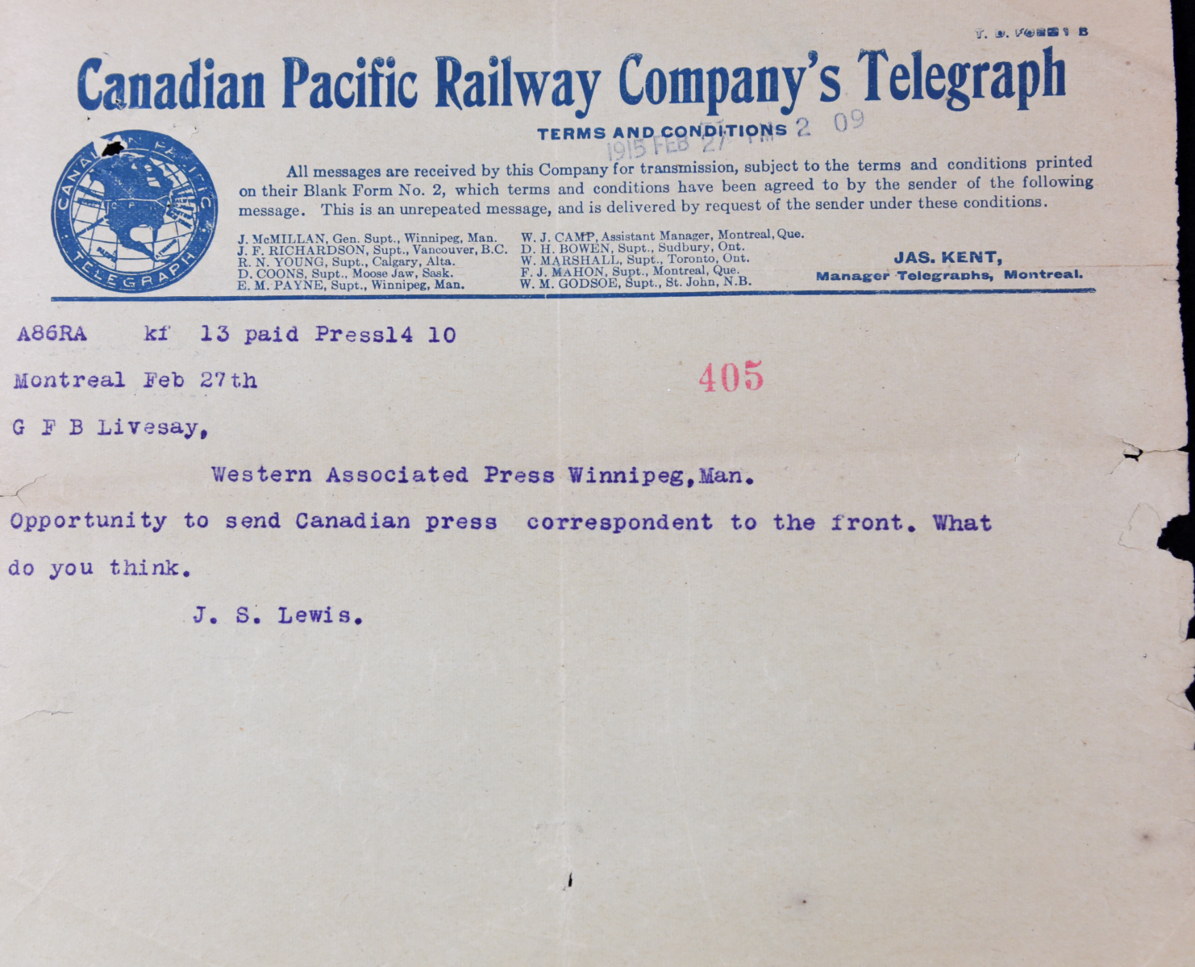

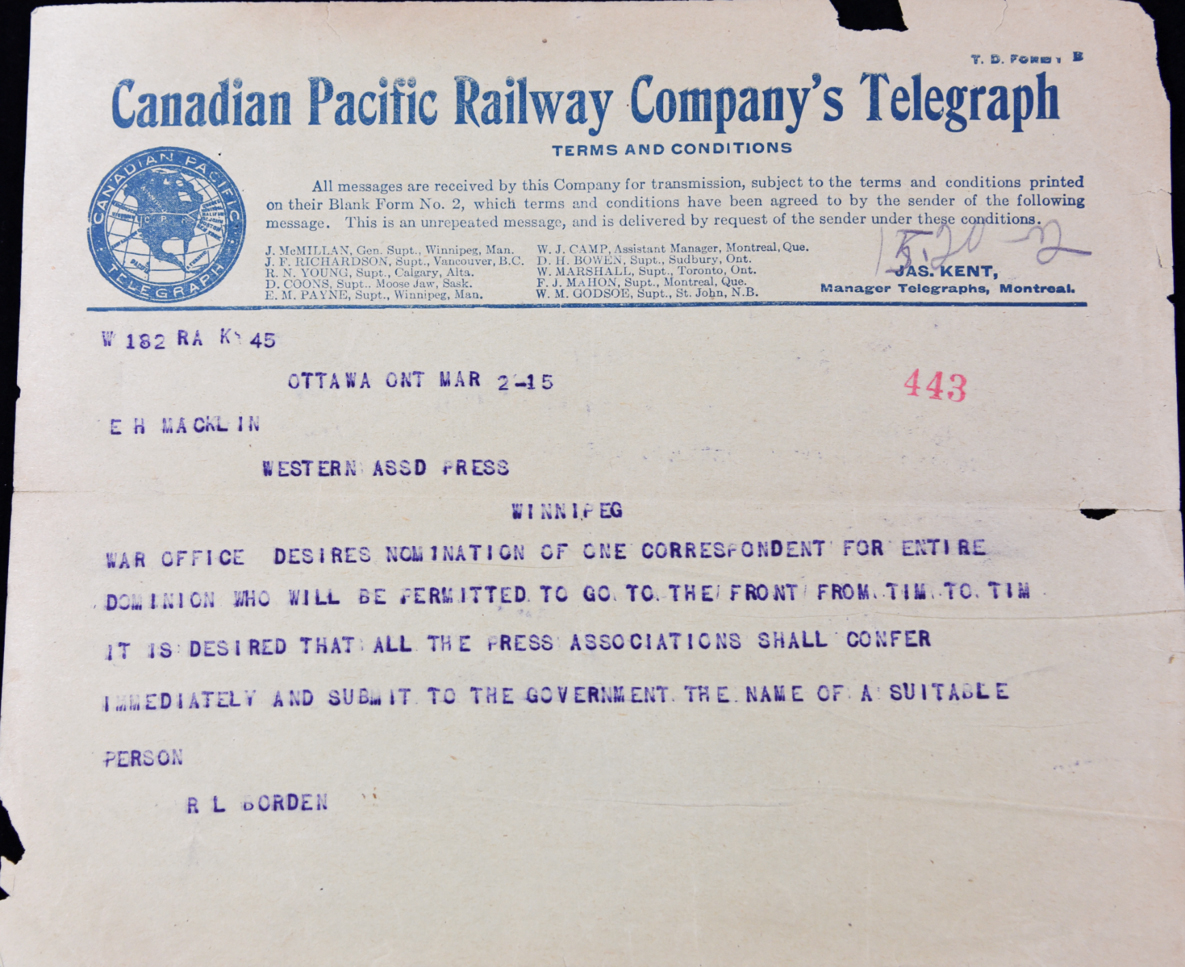

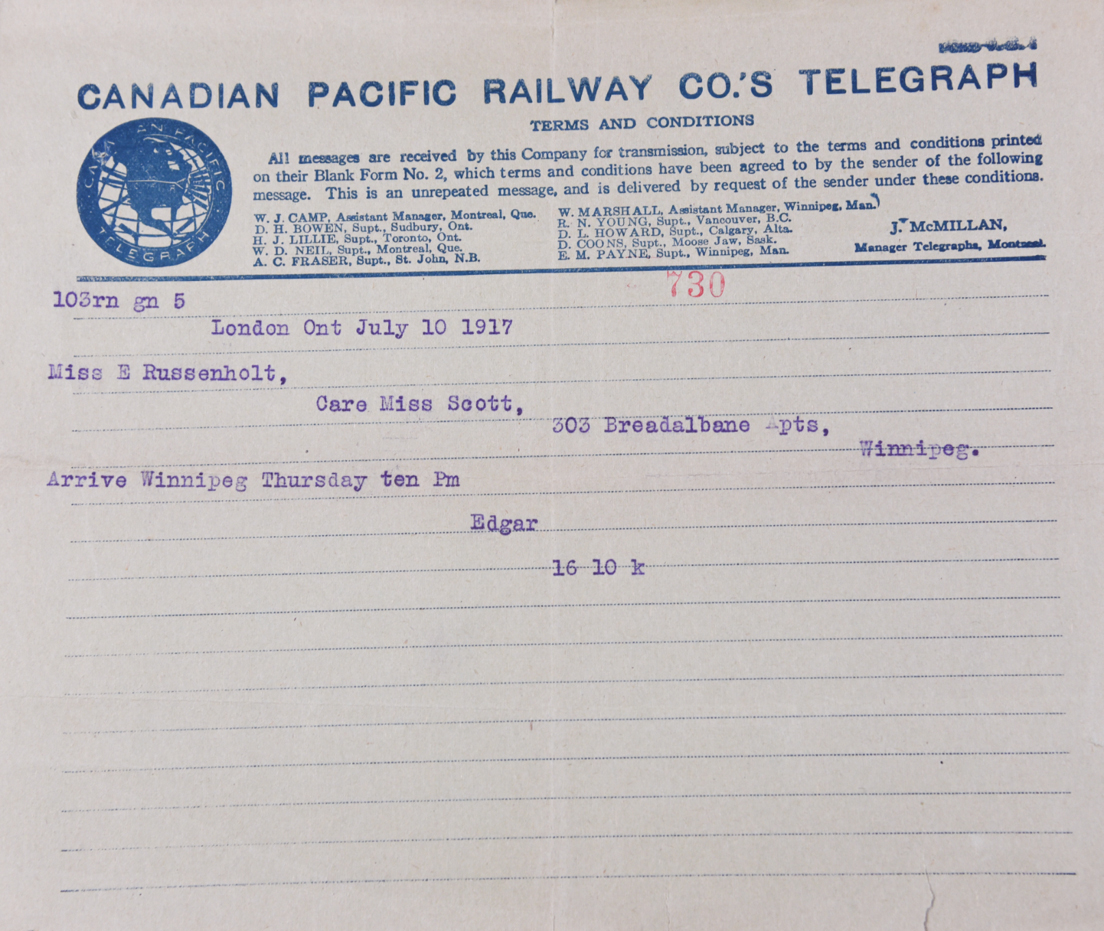

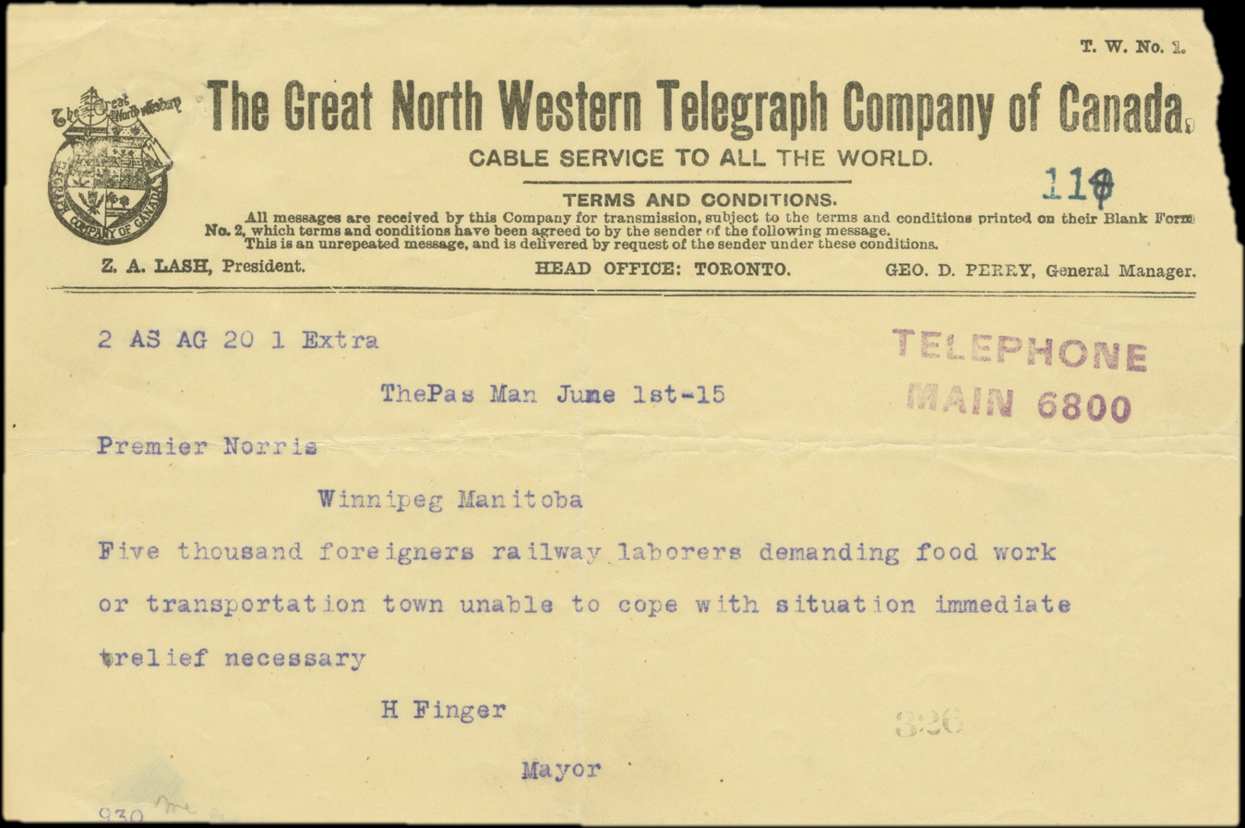

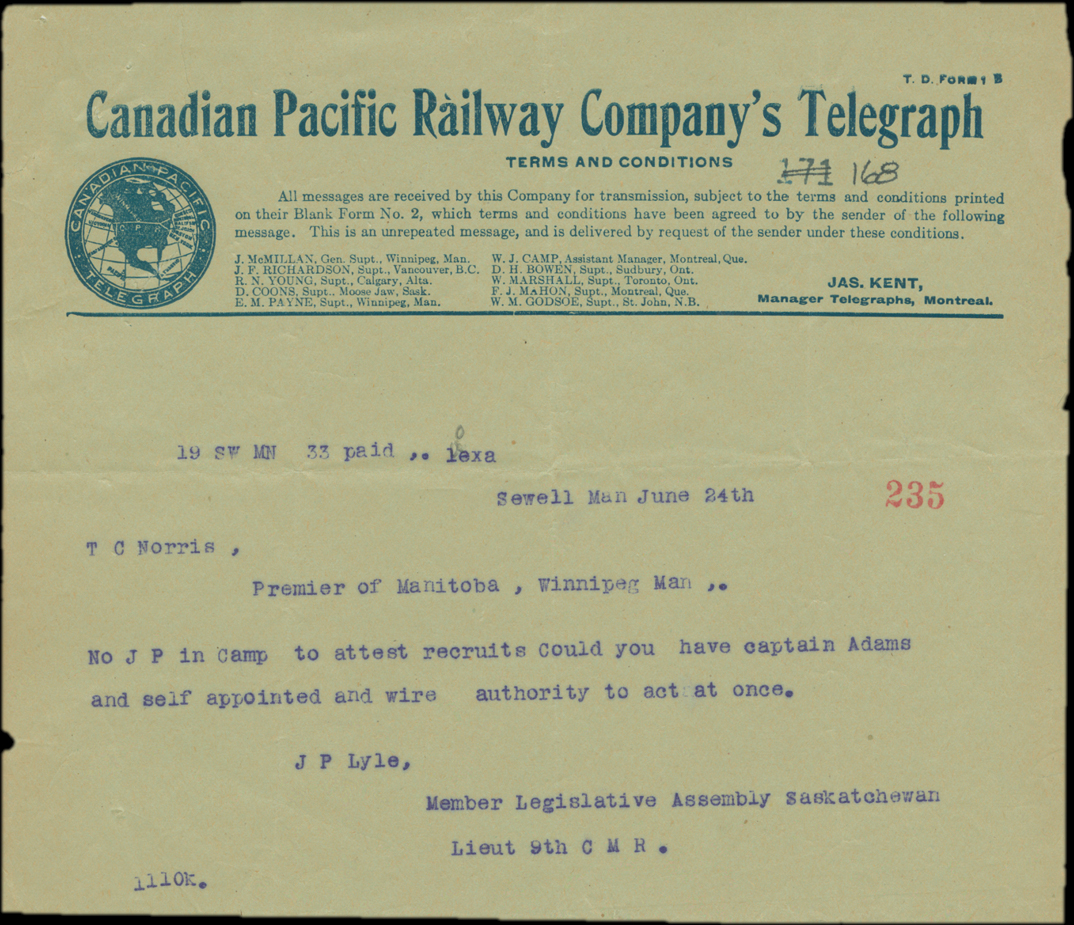

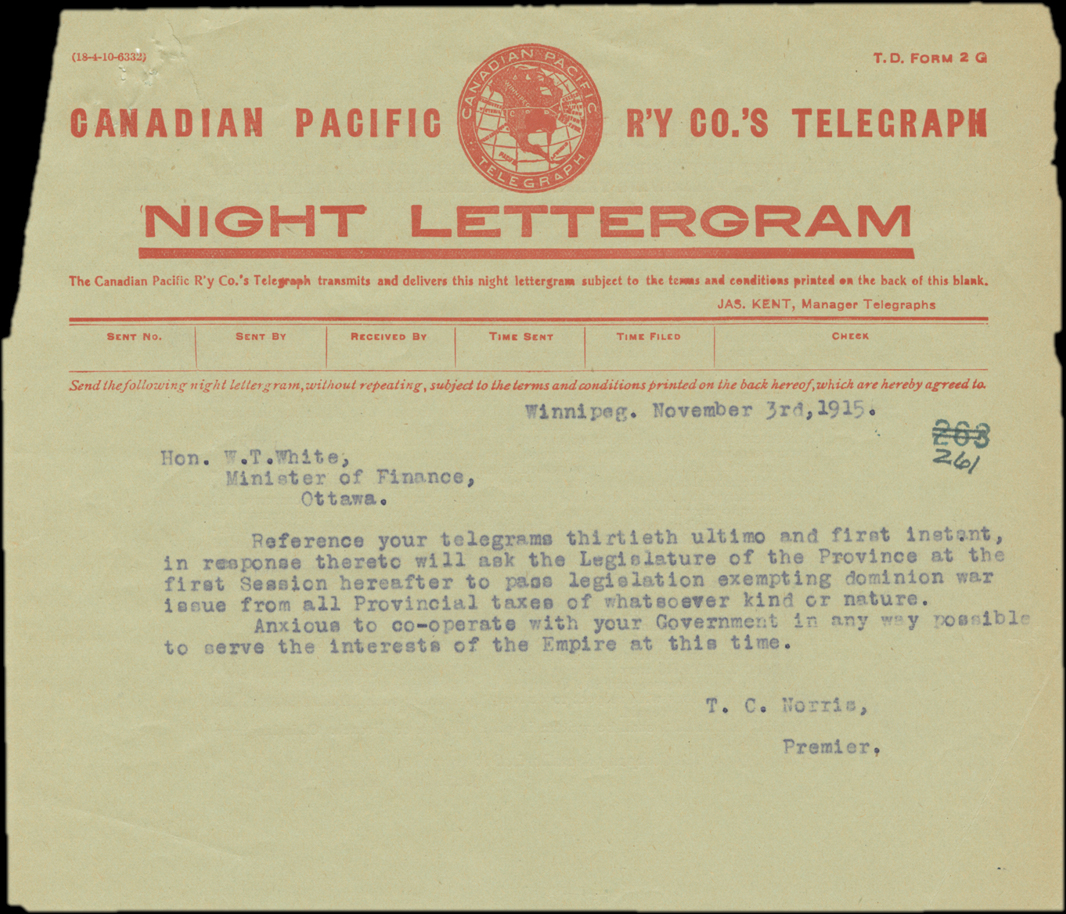

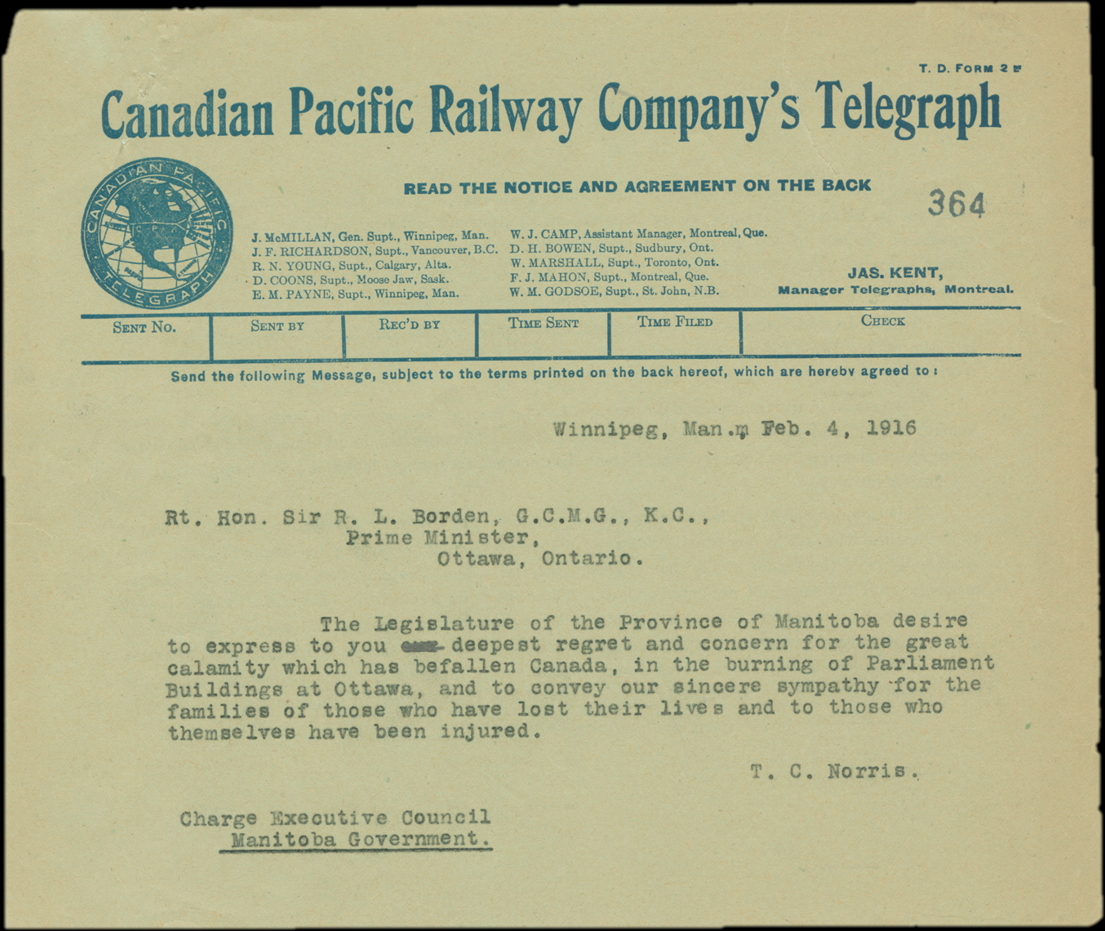

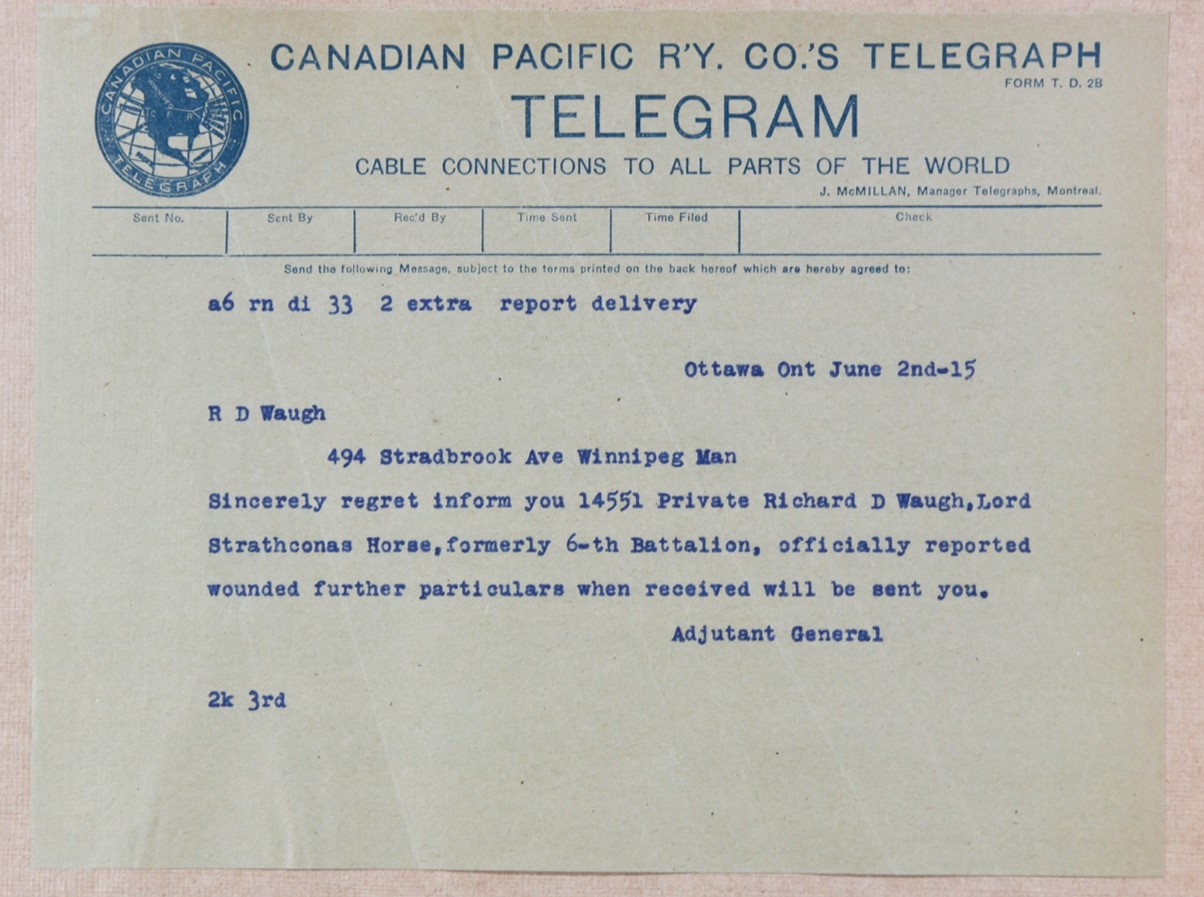

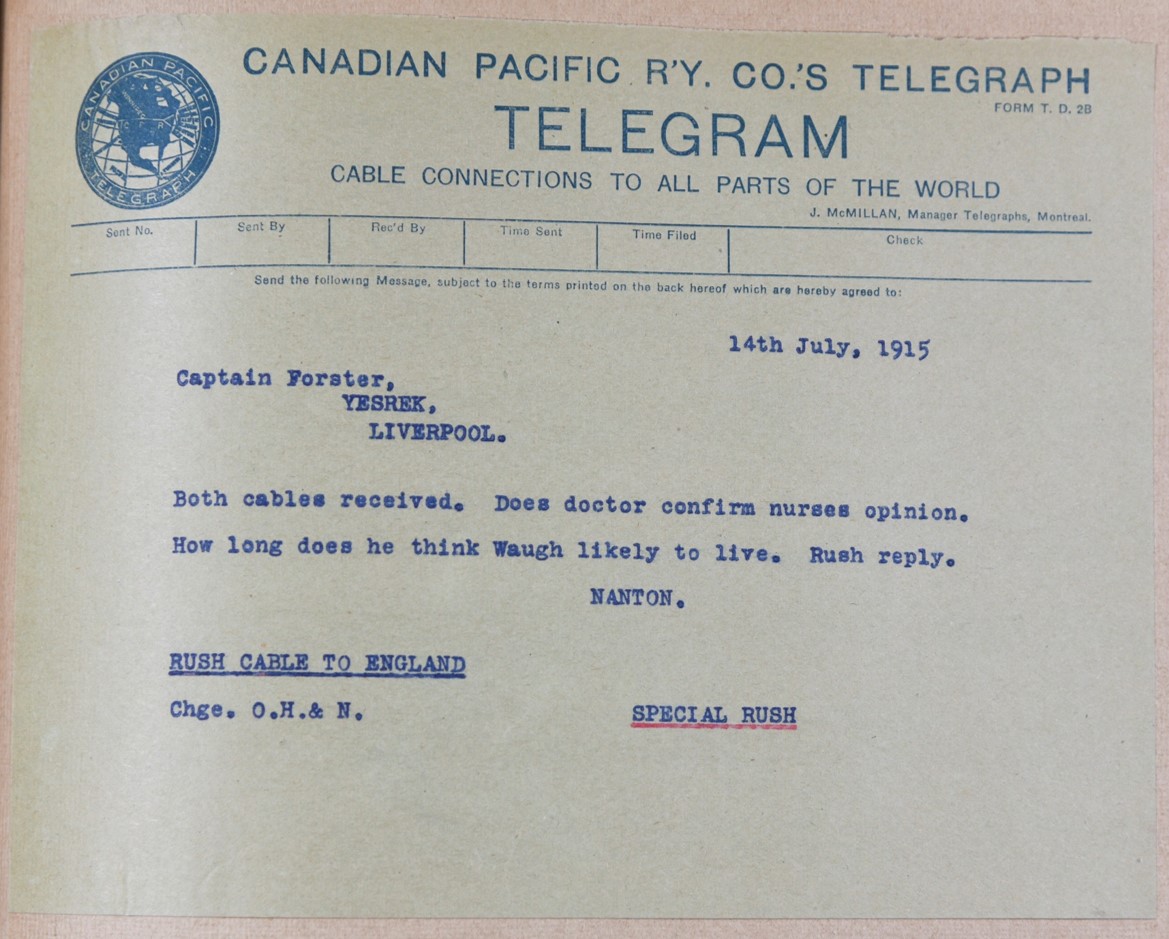

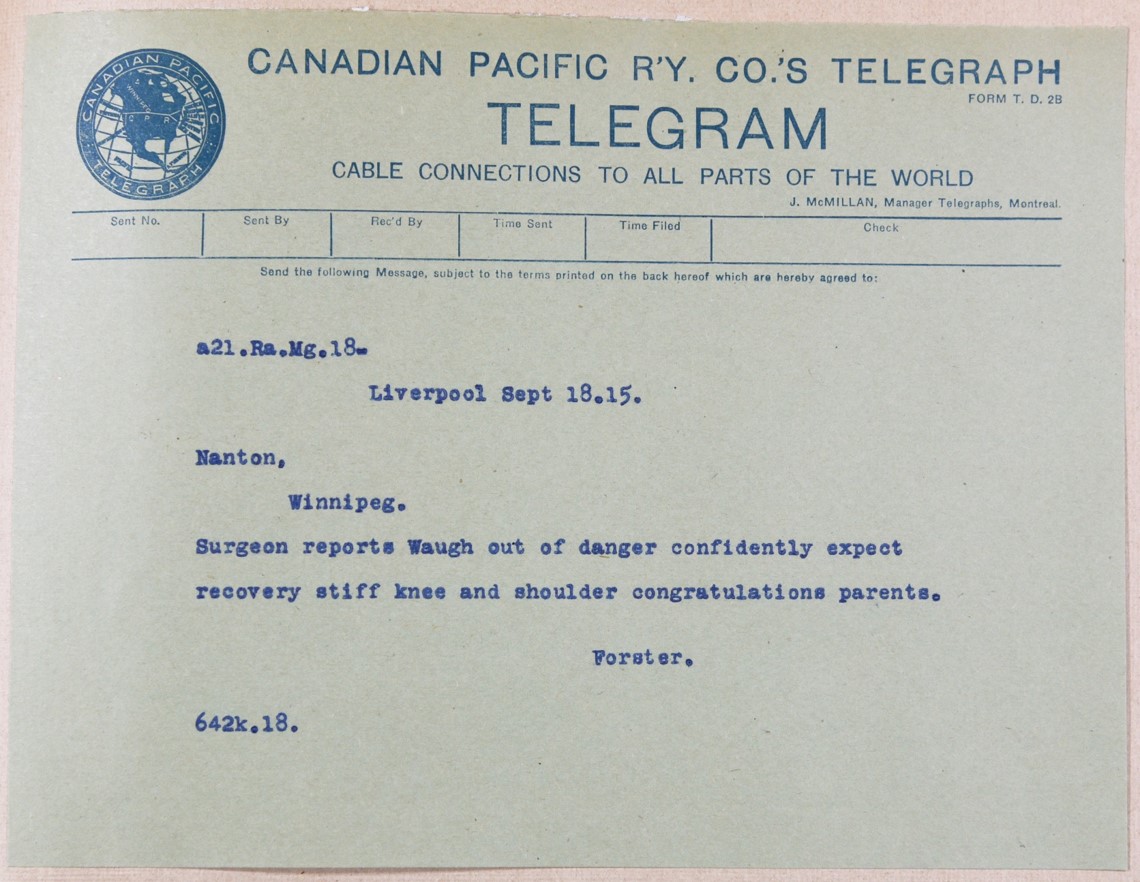

During the First World War, telegrams were the fastest way to send written communication. Telegrams were used by governments and war correspondents needing to communicate quickly and efficiently. They were often used to send notice of a soldier’s death, capture or wounding. Soldiers sent telegrams to let their families know of their travels or that they had survived a battle.

Telegrams, also known as wires or cables, were expensive to send which meant messages were brief, some words were shortened and ‘unnecessary’ words were left out. One hundred years later, telegrams provide an interesting comparison to current forms of fast, abbreviated communications.

Together with our 1918 display, the Archives has also created a slideshow of telegrams from the war. The show can be viewed in the Archives’ foyer during business hours, Monday to Friday, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m and below.

The 20 telegrams featured were chosen from several collections of records at the Archives. Each was sent during the First World War. They include personal telegrams, often with news of Manitoba soldiers at the front; government telegrams from the files of Manitoba Premier T.C. Norris; and telegrams sent to the Canadian Press from war correspondent J.F.B. Livesay.

Search Tip: : Search “First World War” in Keystone to find a wide range of records.

Feedback

E-mail us at [email protected] with a comment about this blog post. Your comments may be included on this page.

7 November 2017

1918: the last year of the war

By 1918, the First World War had been raging for almost 3 ½ years. Canadians had seen major battles and significant casualties and conscription had been enacted. Victory – and the end of the war – was not assured. Twelve months later the war was over and many Canadians remained in Europe to assist with the transition from war to peace.

This week, the Archives of Manitoba launches its final display in a series of First World War displays. This display, entitled “1918: the last year of the war” features a selection of letters, diary entries and photographs documenting nine Manitobans serving overseas in 1918. These Manitobans include soldiers, officers and a nursing sister. The letters and diaries were written in the trenches, in hospital beds and in training barracks and provide both censored and uncensored accounts. The photographs provide a glimpse of the individuals and their surroundings.

This display traces the progression of the year and the war, through winter, spring, summer, fall, Armistice (11 November) and the weeks following to the end of the year. The display includes transcripts so that visitors can read the full text of the letters and diaries featured.

Visit the Archives of Manitoba to see this display or to see other records related to the First World War. We are located at 200 Vaughan Street in Winnipeg, and we are open Monday to Friday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Search Tip: Search “First World War” in Keystone to find a wide range of records.

Feedback

E-mail us at [email protected] with a comment about this blog post. Your comments may be included on this page.

6 November 2017

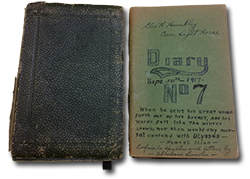

Cavalryman and diarist George Hambley at Passchendaele

George Hambley was another Manitoban who witnessed the battle of Passchendaele although he was not as involved as he had been seven months earlier at the battle of Vimy Ridge. (See the blogs of 23 March 2017 and 11 April 2017 for more information.) Recently returned to the field after a hospital stay, he took care of the horses while many of his fellow cavalryman had been sent with working parties up the line.

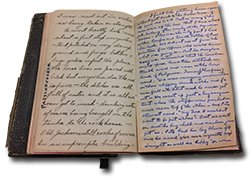

Hambley recorded his experiences in his diary as he did for the rest of the war, and the rest of his life. Like many soldiers at Passchendaele, his first observations were about the mud!

“A most beastly hole – mud about a foot deep everywhere – tent pitched on very damp ground and frogs beetles and bugs galore infest the place. The horse lines are paved with brick but everywhere else the mud is fierce – the ditches are all full of water…”

In what seems to be an account inserted at a later date, Hambley records some of the experiences of his fellow cavalrymen, writing about Tommy (Thompson) and Pete Stewart who walked past a big tent where bodies were packed in rows one on top of the other and:

“Pete Stewart said ‘My God I wouldn’t want to be put in there’ but then he had his leg blown off and he said ‘give me a cigarette boys. I might as well be happy’ or some joke like that. Sure enough they did take his body back to that terrible morgue place. But Pete died like a hero – never a whimper or a complaint. ‘He was a real man.’ Gosh, Tommy said – ‘That was a terrible place for mud. When a shell tore a big hole it would be filled up with water in a few minutes and woe betide anyone who slid down into a shell hole. There were more men lost in the mud I think than were killed by the guns. We should never have been in there at all. The death toll there was terrible.’”

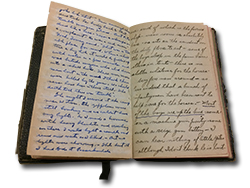

As the Canadian Light Horse left Passchendaele and the Ypres front, Hambley reflected:

“The regiment will not soon forget Passchendaele – especially those who went in on either of the three working parties – I did not have the privilege but would have liked to have been on the machine gun party with Yates.”

For Hambley and the Canadian Light Horse there were more battles ahead.

Search Tip: Search “George Hambley” in Keystone for more information.

Feedback

E-mail us at [email protected] with a comment about this blog post. Your comments may be included on this page.